- Posted: January 3, 2020

- Filed Under: Animal Rights • Politics • Science

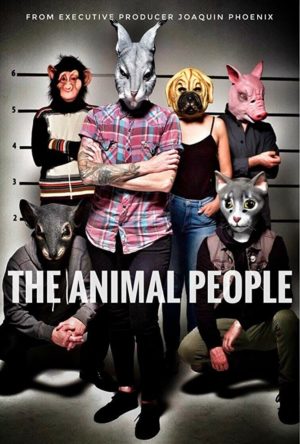

The Animal People is as good an example as you’ll get of a documentary that commits the sin of omission.

The film, featuring executive producer Joaquin Phoenix, tells the story of a group of militant animal liberation activists who led a group called Stop Huntingdon Animal Cruelty (SHAC) in New Jersey who were sent to prison for their activism under federal anti-terrorism laws.

As they tell it, they were victims of an oppressive FBI that was doing the bidding of powerful corporate interests. SHAC, which originally started in the UK, was a protest and harassment campaign against Huntingdon Life Sciences. HLS performed animal research, mostly on rats and mice, that was required under US and European laws and regulations to ensure drug safety. Animal rights activists are strongly opposed to animal research.

The SHAC campaign in the US targeted Huntingdon, as well as those who simply did business with Huntingdon–down to the janitorial staff. It was an aggressive campaign that saw the activists visit people’s homes and publish personal information online in an attempt to bully people associated with Huntingdon.

The SHAC convicts try to distinguish between above-ground activists–them–and below-ground activists who committed economic sabotage or other “direct action,” which they claim they had nothing to do with. They say they merely voiced support for illegal activity, but not do it themselves–a position they believe is protected under the First Amendment. It’s essentially as if they are arguing, “We’re not ISIS–we are just a press office that cheers ISIS on and publicizes their activities.”

The fundamental flaw with The Animal People is that this tale is blown apart by a simple Google search. The SHAC activists appealed their convictions. A federal Court of Appeals ruled against them, and recounted the details of what the SHAC campaign did. Some excerpts:

The SHAC website also posted a piece called the “Top 20 Terror Tactics” that was originally published by an organization that defends the use of animals in medical research and testing. With its standard disclaimer about SHAC not organizing illegal activity, SHAC re-published the list on its website. Some of the tactics included abusive graffiti, posters, and stickers on houses, cars, and in neighborhoods of targeted individuals; invading offices, damaging property, and stealing documents; chaining gates shut or blocking gates with old cars to trap staff on site; physical assaults against the targeted individuals, as well as their partners, including spraying cleaning fluid into their eyes; smashing windows in houses when the occupants are home; flooding houses with a hose attached to an outside tap inserted through a letterbox or window while the home is unoccupied; vandalizing personal vehicles by gluing locks, slashing tires, and pouring paint on the exterior; smashing personal vehicles with a sledgehammer while the targeted individual is inside; firebombing cars, sheds and garages; bomb threats to instigate evacuations; threatening telephone calls and letters, including threats to injure or kill the targeted individual, as well their children and partners; abusive telephone calls and letters; ordering goods and services in the targeted individual’s name and address; and arranging for an undertaker to collect the target’s body. Following the list, the SHAC website stated, “Now don’t go getting any funny ideas!”

…

Sally Dillenback is the senior executive in the Dallas office of Marsh, Inc., an insurance brokerage company that provided services to Huntingdon. She testified that in early 2002, she learned that SHAC had targeted Marsh. In March 2002, Dillenback checked the SHAC website after learning that personal information about employees had been posted there. When she viewed the website, she saw that her personal information had been posted, including the names of her husband and her children, as well as their home address, the name of her children’s school, the make, model and license plate of their personal vehicle, the name of their church, and the name of the country club where they were members.

Shortly after the information appeared on the SHAC website, Dillenback testified that her family began receiving phone calls, often “angry and belligerent,” day and night, as well as a “tremendous” volume of mail. Dillenback testified that one morning, her family awoke to find that pictures of mutilated animals had been glued to the sidewalk in front of her home, as well as the exterior side wall of her home.

Political prisoners? Oppressed activists? Hardly. There’s a lot more in the full opinion.

To the filmmakers’ credit, they let the SHAC leaders undermine themselves on camera. Early in the film, one of the SHAC organizers reminisces about the time the Animal Liberation Front–considered by the FBI to a be a top domestic terror threat–caused $2 million worth of damage to a lab at his university. “It felt like we’d received a visit from somebody really important,” he says, without seeming to have a hint of reflection or remorse. At a later time, he laughs at an old SHAC composition referring to police as “gang members.” Later in the film, one of the SHAC activists mocks the testimony of a witness who was harassed at her home.

The Animal People ultimately is unlikely to sway anyone’s mind. The activists, shouting with bullhorns, are far from sympathetic characters, and their free-speech defense strains credulity. To most viewers, who are neither animal liberation activists nor lawyers, they will come across as unrepentant militants.